As we have seen, Bible writers love to repeat, mirror, or echo earlier themes, scenarios, and phrases. They do this to remind us of God’s saving actions in the past, and show us that He continues to work in the same ways throughout history. No, God does not woodenly repeat himself, but like a great composer writes a symphony, he repeats melodies and phrases but changed in some way—higher, lower, inverted, sideways, or in a new key. We recognize the familiar music, but also appreciate the creativity of the new variations. Joseph and Daniel, both captives, both given the power to interpret dreams, both rise to prominence in their exile. Both will give hope to God’s people, and both will help preserve them. The same basic story line, but with variations. Joseph in Egypt, sold by his brothers; Daniel in Babylon, conquered by Nebuchadnezzar.

And in the story of Ruth, we have seen several story frameworks repeat themselves with charming variations: The Barren Woman, The Firstborn’s Reversal, the Betrothal Narrative. One has already been hinted at: The Sojourner.

Boaz explicitly compared Ruth to the first Sojourner mentioned in scripture, Abraham. In the Sojourner story, God sends or summons someone to a foreign land, not for a time, but for a lifetime. Abraham left the land of his birth, and went to a land God promised to show him. Even at the end of his life, though, Abraham has not yet come into possession of the land of promise. When beloved Sarah dies, Abraham has to haggle, and ultimately pay a high price for, a cave in which to bury his wife.

Joseph and Daniel are sojourners, taken to foreign lands to fulfill God’s design. And though they help provide deliverance and eventual return for God’s people, they will die far from their homelands. Jesus is the ultimate sojourner, not just leaving heaven but his divine powers behind, to dwell as a human with humans, dying at our hands, and being buried in a borrowed grave.

Ruth, born in Moab, sojourns to Israel, where, as she tells Naomi, she will die and be buried. And so she does.

The remaining story framework, The Rejected Cornerstone, we see in both Ruth and Boaz. The near kinsman explicitly rejects Ruth, ironically to preserve his inheritance. Ironically, because his inheritance disappears. We know neither his name, nor the names of any children he might have had. Ruth’s son, however, takes his place in the lineage of David, and ultimately of Christ himself.

Boaz, the text implies, is older than Ruth, and we know of no other wife, despite the fact that he possessed a kind, loving nature, and considerable wealth. Yet he was single. We do not know why, but it may be that, just as Ruth’s Moabite ethnicity made her suspect, perhaps his own ancestry was considered questionable. He was, after all, the son of a well-know prostitute. Rahab, of Jericho. Whatever the cause, he appears rejected also. Great literature, we are told, is usually rich in irony. By that standard, or any other, actually, the Book of Ruth ranks as a masterpiece.

On the one hand, as Boaz tacitly declares, Ruth’s match is Abraham. If he is the “Father of the Faithful,” then Ruth, whose faith mirrors that of Abraham, must be the “Mother of the Faithful.” After all, as Paul points out, to be a son or daughter of Abraham is a matter of faith, not blood.

On the other hand, Ruth’s match must be Boaz himself. In Ruth and Boaz we have an odd couple indeed. An older man, son of a prostitute, marries a woman from the licentious country of Moab. And God blesses their union with a son whose name will live forever! Clearly, these two are “strong partners” for each other. Even so, why rank Boaz so highly? Several of the other women have married great men, or had sons whose names live on, yet we don’t consider their consorts to be nearly as great as the women themselves. Here’s what sets Boaz apart:

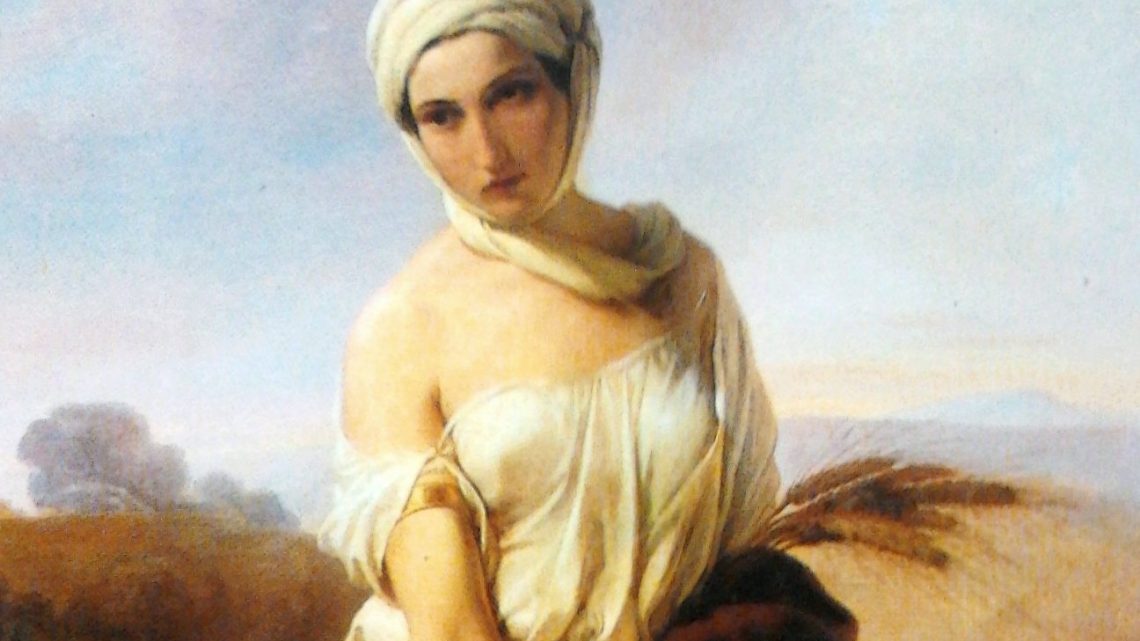

The greatness of most of the women in this book, women of faith and initiative, comes to be recognized only much later. The biblical authors are at pains to demonstrate the greatness of these women precisely because it often went unrecognized, even unnoticed, in their lifetimes. But no small part of Boaz’s greatness is that he recognizes the stunning beauty of character possessed by this unassuming young woman whom he has found gleaning in his field.

“I have been fully told about all that you have done to your mother-in-law since the death of your husband, and how you have left your father and your mother, and the land of your birth, and have come to a people that you didn’t know before.

May Yahweh repay your work, and a full reward be given to you from Yahweh, the God of Israel, under whose wings you have come to take refuge.”

This beautiful benediction not only blesses her, but redounds to his own benefit as well, when she seeks refuge under his ‘wings.’ This, too he recognizes.

He said, “You are blessed by Yahweh, my daughter. You have shown more kindness in the latter end than at the beginning, because you didn’t follow young men, whether poor or rich.

Elsewhere I have written that “Marriage is all we know of heaven.” Contemplating the spiritual beauty of both Ruth and Boaz, it appears this truly was “a match made in heaven.” A bachelor son of a prostitute, and a widow from a licentious culture, both rejected by others—a match made in heaven? How ironic! And how like God, who exalts every valley, makes low every mountain, who declares good news to the poor, sight to the blind, cleansing to sinners, and healing to the broken-hearted! Just exactly the sort of match heaven makes.