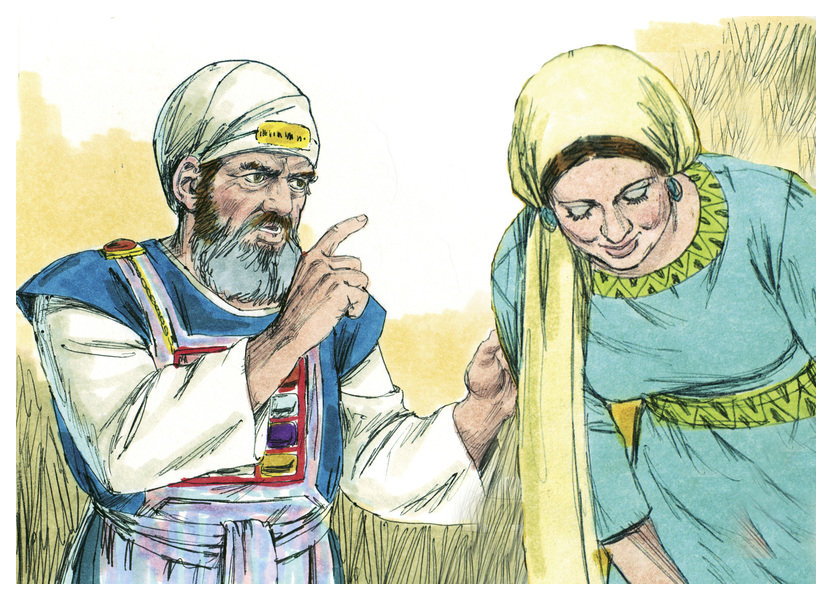

Hannah answered, “No, my lord, I am a woman of a sorrowful spirit. I have not been drinking wine or strong drink, but I poured out my soul before Yahweh.

Don’t consider your servant a wicked woman; for I have been speaking out of the abundance of my complaint and my provocation.”

What a lovely expression: “I have not been drinking wine. . .I poured out my soul.” Remembering that Hebrew poetry features mirrored ideas, rather than mirrored sounds, we recognize this as poetry. It even touches cynical old Eli, who now—after being rebuked by this woman’s quiet piety, and not knowing how prophetically he speaks—performs his role, haltingly—as the messenger who announces the end of barrenness.

Then Eli answered, “Go in peace; and may the God of Israel grant your petition that you have asked of him.”

As John would say of Caiphas many years hence, we say of Eli: “He, being the High Priest . . . prophesied.” God did indeed grant her petition.

When the time had come, Hannah conceived, and bore a son; and she named him Samuel, saying, “Because I have asked him of Yahweh.”

Samuel means “God has heard.”

The man Elkanah, and all his house, went up to offer to Yahweh the yearly sacrifice, and his vow.

But Hannah didn’t go up; for she said to her husband, “Not until the child is weaned; then I will bring him, that he may appear before Yahweh, and stay there forever.”

Quiet in suffering, Hannah remains gracious in success. Some might be tempted to go up to the tabernacle and flaunt her child. But Hannah does not. The scene of her bitter suffering will be one of joy mixed with sorrow too soon. She will bring her treasured child to the tabernacle—but must leave him there. And so it is. She both rejoices that the Lord has granted her a child, and sad to leave him there. As it would be for any parent, she leaves part of her heart there with him, and he never leaves her thoughts.

Samuel ministered before Yahweh, being a child, clothed with a linen ephod.

Moreover his mother made him a little robe, and brought it to him from year to year, when she came up with her husband to offer the yearly sacrifice.

Every year she makes a robe for Samuel, each year a little larger. Stitch by stitch, week by week she sews the robe for her son, no longer in her home but always in her heart.

Belatedly, Eli recognizes the hand of God upon Hannah, and consciously preforms his prophetic function:

Eli blessed Elkanah and his wife, and said, “May Yahweh give you offspring from this woman for the petition which was asked of Yahweh.” Then they went to their own home.

Yahweh visited Hannah, and she conceived, and bore three sons and two daughters.

In some ways, this seems a simple story. After all, there are many barren women, both in scripture and in real life. But in most of these stories that end positively, God retains the initiative. Already we have encountered three barren women who took the initiative: Tamar, Naomi, and now Hannah. In each case, God expressed his approval by granting their desires, and more. More, because Tamar does not just have a child, she becomes progenitor of Christ, as does Naomi. Hannah does not: Elkanah is from the tribe of Ephraim, not Judah. But Hannah’s child becomes one of the greatest judges. And though he is not in the kingly line, he is the anointer of kings.

Ordinarily, royalty is conferred at birth, by virtue of being born son of a King. But neither Saul nor David were born sons of a king. So Samuel becomes father in proxy to both Saul and David, for it is he, through anointing, that confers royalty upon them. And Hannah’s petition makes all this possible.

Samuel is not only one of the greatest—and the last—of the judges, but he also begins his duties as judge at an early age. This is Hannah’s story, not Samuel’s so we will omit some of the details. But we all remember how God called Samuel’s name as the boy slept. When eventually Eli realized it was God speaking to Samuel, and instructed him how to respond, God gave the young boy this message to deliver to the High Priest.

Yahweh said to Samuel, “Behold, I will do a thing in Israel, at which both the ears of everyone who hears it will tingle.

In that day I will perform against Eli all that I have spoken concerning his house, from the beginning even to the end. For I have told him that I will judge his house forever, for the iniquity which he knew, because his sons brought a curse on themselves, and he didn’t restrain them. Therefore I have sworn to the house of Eli, that the iniquity of Eli’s house shall not be removed with sacrifice or offering forever.”

These are fearful tidings for anyone to deliver; all the more so for one just a lad, and he must tell these terrible judgements of the High Priest to his face! God had communicated these things directly to Eli previously. Why does he now repeat them through Samuel? Because, young as he is, Samuel has become the Judge of Israel. Sending this message through him ratifies Samuel’s calling and status, and signals the passing of authority from the old priest to the young boy.

Samuel grew, and Yahweh was with him, and let none of his words fall to the ground.

All Israel from Dan even to Beersheba knew that Samuel was established to be a prophet of Yahweh. Yahweh appeared again in Shiloh; for Yahweh revealed himself to Samuel in Shiloh by Yahweh’s word.

Eli still lives, but no longer serves as Judge. The young Samuel has taken his place, and in the next chapter of 1 Samuel, Eli and his sons will die. Samuel will stand out as Judge, even among such as notables as Gideon and Samson. Indeed, “Yahweh . . . Let none of his (Samuel’s) words fall to the ground.” An amazing testimony.

We do not know the names of any of Elkanah’s other children; only Samuel. Samuel was indeed “better than ten sons.” All because of Hannah’s prayers. And it is these prayers that determine Hannah’s “strong partner.” Later there will be another figure arrive at a time when corruption has infected Israel’s leadership, and this man, a nobody from nowhere, will initiate through his prayers an amazing reformation in Israel. Oddly enough, it is the apostle James who tells us how this great movement began:

Elijah was a man with a nature like ours, and he prayed earnestly that it might not rain, and it didn’t rain on the earth for three years and six months.

He prayed again, and the sky gave rain, and the earth produced its fruit.

Elijah, a ‘nobody from nowhere?’ Actually, yes. We have no information about Elijah, his parents, what tribe he is from. Although he is called “the Tishbite,” we do not know if that tells us his hometown, or is a nickname, say, like “Honest Abe.” He appears suddenly, at the court of Ahab, and disappears almost as suddenly. After a time of less than five years, he disappears on a chariot of fire. So far as we know, he has neither famous ancestors, children, nor does he come from a famous city.

In human terms, he’s a nobody, from nowhere. Elijah, regarded as the greatest of the prophets, whose prayers brought about reformation in Israel, provides an apt match for Hannah, whose prayers made her the mother of one of the greatest Judges, who reformed Israel, and anointed Kings.

And that, it seems to me, is the ultimate message of Hannah and Elijah. When I read that “The effectual fervent prayer of a righteous man availeth much[James 5:16, KJV],” I always assumed that the “righteous man (or woman)” in question must be Somebody. A prophet, a pastor, a teacher, an elder—somebody important. But Hannah’s story tells me that the fervent prayers of any faithful person, a nobody from nowhere—can change history.