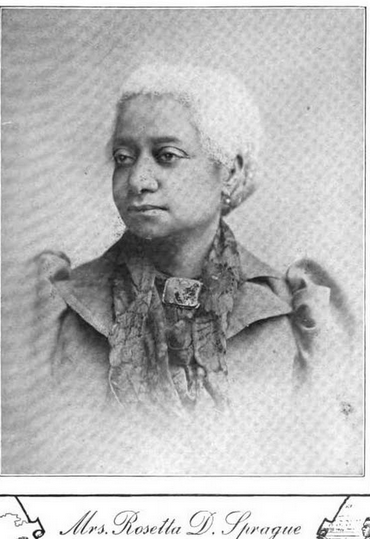

Writing to Ellen G. White in 1903, Judson S. Washburn, pastor of the Second Seventh-day Adventist church in Washington, DC, noted that Rosetta Douglass Sprague, the daughter of Frederick Douglass, was among the “prominent colored members” of the First Seventh-day Adventist church (First Church). Founded on February 6, 1889, by Willard Saxby, First Church was an unusually integrated congregation of African Americans and whites, well known for its outreach to the city’s poor and suffering. (Read more about this remarkable congregation in Douglas Morgan’s “’They Preach a Political Gospel:’ The Prophetic Witness of Washington, D.C.’s Earliest Seventh-day Adventists.”)

Rosetta Douglass Sprague joined the Adventist Church late in life, and her role in the activities of First Church remain lost to history. However, her life was remarkable in its own way.

A Remarkable Education

Born on June 24, 1839, in New Bedford, Massachusetts, to Frederick and Anna Murray Douglass, Rosetta joined the family less than a year after her father gained his freedom through her mother’s assistance. Rosetta’s early years were spent in Lynn, Massachusetts, and Rochester, New York.

Being the eldest child of a gifted celebrity presented numerous challenges. According to Rosetta’s own account, at the age of six she was sent to Albany, New York, to be privately tutored for two years by Abigail and Lydia Mott—cousins of the Quaker abolitionist and feminist Lucretia Mott. The move was intended to relieve her mother of the burden of caring for one of her four children while Frederick Douglass toured and lectured in Europe in an effort to protect him from bounty hunters in the United States. Meanwhile, Anna raised three boys, supported them by making shoes, and established headquarters for the Underground Railroad in Rochester. She had been active in the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society when the family lived in Lynn. All of this almost without even a rudimentary education. Rosetta clearly admired her mother’s ingenuity, hospitality, and activism. (Read her moving memoir, “My Mother as I Remember Her.”) However, Frederick Douglass had even higher expectations for his children and, by some accounts, for his daughter in particular.

Frederick Douglass may have had another reason for sending Rosetta to Albany for a private education. In 1845, the Rochester public schools were segregated, and he was determined his daughter would have a better education than offered in the school provided for African American children. The Douglass children were often taught by private tutors including another Quaker governess, Phebe Thayer, in Rochester. By 1848, Rosetta was prepared to study at the Seward Seminary, a prestigious girls’ school in Rochester. Later, she trained to become at teacher at Oberlin College and the Salem Normal School in Massachusetts. It was an exceptional education for a woman at the time, even more notable for an African American daughter of a formerly enslaved man.

Rosetta’s exceptional education was intended to prepare her to join in her father’s work for the advancement of their fellow African Americans. She often served as her father’s assistant, folding pamphlets, taking dictation, and imbibing his views on racial justice, equality, and religion. However, her life soon took a different path.

Tumultuous Marriages

In 1862, Rosetta traveled to Philadelphia where she hoped to find work as a teacher. Unsuccessful in this quest, she moved to Salem, Massachusetts, where she did teach in the public school for brief time. It was while she was teaching in Salem that she met and married Nathan Sprague (1841-1907) on December 24, 1863, a formerly enslaved man turned Union soldier who served in the Massachusetts 54th (Colored) Regiment. It proved to be an unequally yoked marriage. With little education and few skills, Nathan bounced from job to job, unable to maintain any profitable work for long. While working in the post office, he was caught opening letters and stealing the contents. For this he served one year in a penitentiary. Thus, Rosetta raised her seven children in often difficult circumstances, falling back on the support of her parents when necessary.

Although Rosetta would finally become a public speaker in her later years, most of her adult life was not the life Frederick had envisioned for his daughter. Frederick Douglass’s biographers have tended to disparage Nathan Sprague; however, caught between her father and her husband, Rosetta herself believed circumstances frequently worked against her husband through little fault of his own. Her father’s opinion may have held some merit as after the Spragues relocated to Washington, DC, in the late 1870s and Nathan became a real estate agent, he was frequently entangled with charges of fraud and larceny.

In turnabout, Rosetta was not happy about her father’s remarriage in 1884. Following Anna’s death in 1882, Frederick married white suffragist Helen Pitts. Many friends of the couple as well as Frederick’s children objected to the marriage on the grounds of race. Helen was also young enough to be his daughter. When Frederick died in 1895, his will was contested in a battle between Helen and the Douglass children. The will left his property to Helen, but lacked the required witnesses. Rosetta was embroiled in this legal battle around the time she joined the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

Family Faith

In Rochester, the Douglasses were members of the Methodist church. Adventists have frequently noted Frederick’s belief that the falling stars of 1833 were a “harbinger of the coming of the Son of man.” His proximity to Adventists in New Bedford, Massachusetts (home of Joseph Bates), and Rochester, New York (the center Advent work from 1852 to 1855—the Millerite message was preached here in 1843), after escaping slavery in Maryland also gave rise to the idea that he was aware of the Advent message. But Frederick’s relationship with Christianity was much more complex than these brief references convey. He saw American Christianity as complicit in the crime of slavery and believed it to fall far short of the biblical ideal. Thus, the daughter who did not fully live up to her father’s dreams, came full circle in adopting a radical faith that sought to reclaim the purity of the biblical ideal. Shaped by her father’s influence, Rosetta must have hoped the Adventist Church would provide a haven for all people regardless of race or color and that it would preach racial justice toward the goal of uniting all people as equals in Christ. Tragically, the unconventional interracial community of First Church came under criticism instead, which led to division and the establishment of the Second Seventh-day Adventist church in Washington, DC.

Rosetta Douglass Sprague died in Washington, DC, on November 25, 1906. She was buried in Rochester, New York, her grave forgotten and overlooked until it was rediscovered in 2003.